How many infiltrators are there in Israel?

According to the Population and Immigrant Authority, at present there are

37,288 infiltrators in Israel.[1]

71% of the infiltrators are citizens of Eritrea (26,563).

21% of the infiltrators are citizens of Sudan (7,624).

7% are citizens of other countries in Africa.

1% are citizens of the rest of the world.

These figures provided by the Population and Immigrant Authority do not

include children born in Israel to Eritrean or Sudanese parents. According to

aid organizations helping the infiltrators, there are approximately 8,000 such

children. The above statistics does not include infiltrators who did not register

when entering the country. In addition, a substantial number of tourists

entered Israel in order to reunite with members of their family who infiltrated

into Israel, and have remained in Israel illegally – their visas long expired.

Infiltrators, asylum seekers or refugees?

Infiltrator: The legal definition derived from the Prevention of Infiltration Law

states: “A person who is not a resident of Israel, who entered Israel not by way

of a border crossing.”[2] An ‘infiltrator’ is the formal term and the most neutral

as it describes the way of entrance into the country. The Supreme Court

judges also use this legal term.

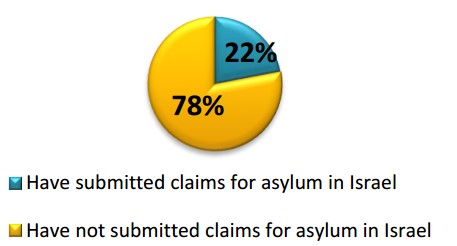

Asylum seeker: Only a small number of the infiltrators, 22%, are asylum seekers – i.e. they have filed a claim for refugee status on the grounds that their lives and freedom are at stake in their country of origin; their claims have yet to be reviewed. In other words: 78% of the infiltrators have never submitted a claim for asylum.[3]

It should be noted that the filing of a claim is not an indication of the

applicant’s situation in his or her country of origin, but purely a submission of

a claim. Most of the claims for asylum around the world are denied.

Refugee: Someone whose claim for asylum has been reviewed and accepted

and is thereafter recognized by the state as being entitled to protection.

[1]Population and Immigration Authority, (2018). Foreigners in Israel statistics, table 3

https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/foreigners_in_Israel_data_2017_2.pdf

[2]Prevention of Infiltration law (1954). Amendment no. 3

https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/Law01/247_001.htm#Seif1

[3] As of August 2017, of the 64,850 infiltrators entering Israel, 14,318 had applied for asylum. Population and

Migration Authority, (2018). Data of foreigners in Israel, Table 2.

https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/foreigners_in_Israel_data_2017_2.pdf

Does Israel allow submissions of claims for asylum? Why have the claims already submitted not been reviewed by Israel?

The allegation that Israel does not allow claims for asylum to be submitted is

incorrect. Up till 2013, because of the huge influx of infiltrators into Israel, the

country granted group protection, or adopted the ‘temporary exclusion’

policy, towards all Eritreans and Sudanese with no exceptions, thus not

allowing them to submit individual claims for asylum. From 2013 until the

beginning of 2018, for approximately 5 years, Israel allowed anyone who so

desired to submit a claim for asylum. The infiltrators in Israel were made

aware of this option, which was even publicized by the United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees, and thousands took advantage of it.[4]

Approximately 80% of the infiltrators in Israel have never bothered to apply

for asylum. The reason for this is that they prefer to continue benefiting from

the rights Israel grants them under the group protection which includes the

protection of labor laws, subsidized health care for their children, free

education, etc. Presumably the infiltrators do not want to risk losing their

status if their claim is denied. Anyway, even if there are other possible

explanations, it is all speculation. The only indisputable fact is that most of the

infiltrators have never submitted claims for asylum.

However, the State reviews claims for asylum at an extremely slow pace; the

Israeli Immigration Policy Center is demanding an increase in the pace for

reviewing the claims.

[4] UNHCR: Application for asylum in Israel (2015), (Facebook Page “Refugees in Israel”)

https://web.archive.org/web/20180208151839/https://www.facebook.com/RefugeesInIsrael/photos/a.5131864954073

73.1073741828.511268008932555/879961562063196/?type=3&theater

Why is the percentage of recognition so low?

It is an undisputable fact that up till now Israel has only granted refugee

status to 12 Eritreans and Sudanese. This is a low recognition rate. On the one

hand, Israel has adopted a limited interpretation policy and does not

recognize desertions from the Eritrean army as grounds for receiving refugee

status, focusing only on personal persecution due to religion, ethnic origin,

etc. On the other hand, Israel has granted humanitarian status to 1,100

Darfuris, granting them temporary residency which confers on them the same

rights as recognized refugees. This is in contrast to the growing international

trend of rejecting claims for asylum from Sudan. For example, a joint report

from the Danish and British governments determined that most of the

Darfuris can return to Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, without any fear.[5]

Therefore, taking the Darfuris into consideration, Israel has granted status to

at least 73.6% [6] of the asylum seekers, and has declared that more Darfuris will

be granted status in the near future.

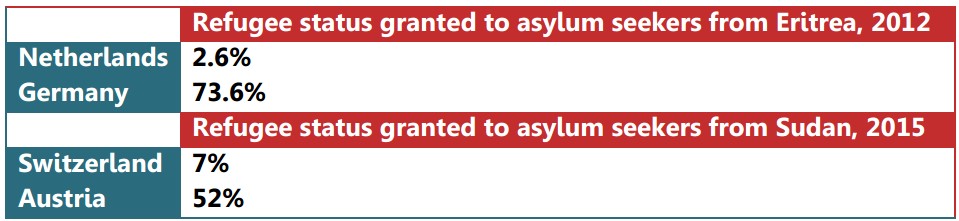

In general, it is important to understand that there are differences in the

policies for recognizing refugees, not only between Israel and countries in

Europe, but also between different countries in Europe itself. The gap stems

from the choice of adapting either a limited or expansive interpretation of the

international conventions.

More about the gaps can be learnt from the data provided by UNHCR.

In 2012 Netherlands granted refugee status to only 2.6% of the Eritrean

asylum seekers, while Germany recognized 73.6%.6 In 2015 Switzerland

recognized only 7% of the Sudanese asylum seekers (11 out of 161 claims for

asylum), while Austria recognized 52%.[7]

It is imperative to point out, that contrary to the one-sided picture the aid

organizations for infiltrators paint, the State of Israel plays an important and

active part in the international effort to help refugees. Israel has provided

medical treatment to thousands who were wounded in the civil war in Syria,

awarded citizenship to around 2,000 of the South Lebanese Army soldiers and

sends rescue and aid missions to disaster areas around the world, etc.

Finally, the State of Israel, setting itself apart from Europe, has granted

protection against deportation to their country of origin for 100% of the

Eritreans and the Sudanese. This status has allowed them to work legally, to

receive health insurance at their employer’s cost, free education for their

children, subsidized day care, health insurance for their children, partial access

to grants provided by the National Insurance, etc. This protection was

recognized in the statistical files of the UNHCR as ‘refugee-like’ status. [8]

[5] UK home office, Danish Immigration Service, (2016). Sudan – Situation of persons from Darfur, Southern Kordofan

and Blue Nile in Khartoum.

https://www.nyidanmark.dk/NR/rdonlyres/18692451-D506-4A5F-8FE2-

32E5A2F3658B/0/SudanFFMreportJune2016.pdf

[6] UNHCR, (2013). Statistical Yearbook 2012, Annex, pg. 110-111 table 12 http://www.unhcr.org/52a723f89.html

[7] UNHCR,(2017), Statistical Yearbook 2015, Pg. 90 table 12

http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/country/59b294387/unhcr-statistical-yearbook-2015-15th-edition.html

Why are the infiltrators not deported back to their country of origin if they are not refugees?

Sudan: Israel cannot send Sudanese infiltrators back to Sudan, even if the

claim for asylum has been reviewed, and it has been determined that they are

not entitled to protection. This is because Israel has no diplomatic relations

with Sudan, which considers the State of Israel an enemy state and therefore

does not allow Israel to deport these infiltrators directly. Whilst most are not

refugees, the current global trend is to make things more difficult even for

those who have emerged from conflict zones like Darfur. However, citizens of

Sudan can return to their home country from Israel through a secondary

country. According to the Immigration and Population Authority’s statistics,

many Sudanese have already returned to Sudan.[9]

Eritrea: Israel has not deported Eritrean infiltrators back to their country

because Eritrea is only willing to accept citizens who have been in exile and

return of their own free will. A report by the EASO, an official development

institute of the European Union working to delineate a unified asylum policy

for all European Union countries, shows that any infiltrator willing to pay a 2%

tax on their income, to write a letter of remorse and to regulate their status

with the authorities may return to their homeland, without fear. In other

words, they return only of their own free will. [10]

[8]UNHCR (2014). Statistical Yearbook 2013, Annex. Pg. 79 table 1

http://www.unhcr.org/54cf9bc29.html

[9] Population and Immigration Authority, (2018). Foreigners in Israel statistics.

https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/foreigners_in_Israel_data_2017_2.pdf

[10] EASO (2016). Country of Origin Information Report: Eritrea National service and illegal exit.

https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/COI-%20Eritrea-Dec2016_LR.pdf

One possible explanation for this policy is that one third of Eritrea’s GNP

(Gross National Product) is derived from the money the Eritrean immigrants

around the world send to their families. It’s even safe to say that the Eritrean

emigrants are almost the country’s sole export industry. Therefore the

government has a huge economic interest in broad labor migration and is not

interested in the forced return of its citizens, especially as it will then

contribute to the loss of the above source of income.[11]

For that reason we, the Israeli Immigration Policy Center, promoted the

‘deposit law’. This law demands that all employers deposit 20% of the

infiltrator’s wage to a designated bank account – an amount which they can

take on their departure. This has resulted in more than 2,000 Eritreans

independently returning to their country of origin.[12]

In general, many factors make it difficult to deport infiltrators back to their

country of origin. However, these factors are not enough to prove that their

lives are in danger. In addition, there may be cases where, even though the

asylum seeker is in danger, they have not met the UN’s convention criteria of

refugee status and therefore are not entitled to this status.[13] In these cases, it

is the obligation of the State to refrain from sending them back to their

country of origin. However, within the framework of appropriate agreements,

the country has a sovereign right to deport the infiltrator to a safe third

country.

[11] Chatham House, (2007). Eritrea’s Economic Survival. Pg. 15

http://www.africanidea.org/eritrea.pdf

[12] Ester Tsegay Gerassgehr v. The Knesset: Response on behalf of the State (2017), HCJ 2293/17, Israel: Supreme

Court, p.32. available at:

https://www.acri.org.il/he/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/bagatz2293-17-asylum-seekers-wages-meshivim2-4-1117.pdf

[13] Nessnet Aregai Assafo v. Ministry of Interior (2012), Appeal of Administrative Petition 8908/11, Israel: Supreme

Court, available at:

http://elyon1.court.gov.il/files/11/080/089/M09/11089080.M09.htm

Why does Israel deport only Africans?

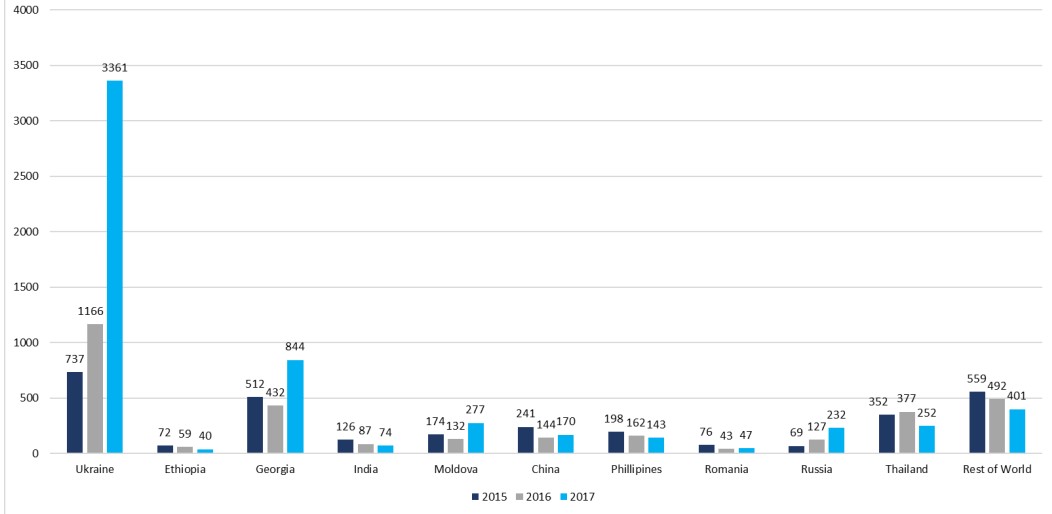

This is a false claim as not only Africans are being deported. On the contrary,

most of those deported each year come from East Europe, and only a minority

is from African countries. In 2017, according to data from The Immigrant and

Population Authority, of the 5,841 illegal immigrants deported from Israel,

most were from Europe and Asia: 3,361 were Ukrainian citizens, 232 Russians,

and 252 were citizens of Thailand. [14]

The deportation of illegal immigrants from Israel

according to country of origin and year:

[14] Population and Immigration Authority, (2018). Foreigners in Israel statistics. Pg. 22-23

https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/foreign_workers_stats/he/foreigners_in_Israel_data_2017_2.pdf

Is Israel condemning the infiltrators to death by sending them to a third country?

The answer is plain and simple – no. The third countries, Uganda and Rwanda

(according to foreign publications), are defined by the UNHCR as

governments which has adopted among the most progressive policies

worldwide to support refugees.[15] In the above countries, no infiltrator is

condemned to die, enslaved or persecuted. Based on a small number of

anonymous statements by infiltrators who have left Israel, the aid

organizations claim that in the above two countries, the infiltrators were not

allowed to stay and were forced to risk their lives trying to make their way to

Europe. This claim was rejected by the District Court and the Supreme Court,

both stating unanimously that there was no basis to this accusation. The

District Court even criticized the evidence, calling it biased and unreliable.[16]

The Supreme Court criticized the methodology used to write the statements.[17]

In addition, the District Court determined that it was in the interest of the

infiltrators to report that they had no option to remain in the countries, in

order to gain status in the countries they moved onto.[18]

The Supreme Court acknowledged that some of the infiltrators chose to try to

immigrate to Europe, with all the dangers involved, but stated that the

immigration was done on their own free will. With regards to the former, the

President of the Supreme Court, Miriam Naor, stated that the moment

infiltrators were granted status in a safe country, yet chose to move on to

another country, the responsibility of the State of Israel expired.[19]

[15]UNHCR, (2017), The Right of Refugees to Work in Rwanda.

http://www.unhcr.org/rw/12164-right-work-refugees-rwanda.html

[16] A.G.T v. The State of Israel – Ministry of Interior (2015), Administrative Appeal 5126-07-15, Israel: Court of

Administrative Affairs in Beer Sheva, Par. 22 of the judgment of Justice Rachel Barkai. available at:

https://www.nevo.co.il/psika_html/minhali/MM-15-07-5126-416.htm

[17]Almessged Gereyosous Tsegette v. Interior Minister (2017) Appeal of Administrative Petition 8101/15, Israel:

Supreme Court. Par.56 of the judgment of the president Naor. available at:

http://elyon1.court.gov.il/files/15/010/081/c29/15081010.c29.htm

[18]See reference no 16

[19]Almessged Gereyosous Tsegette v. Interior Minister (2017) Appeal of Administrative Petition 8101/15, Israel:

Supreme Court. Par.66 of the judgment of the president Naor